Pandemics are a persistent threat to global health and stability. They represent large-scale outbreaks of infectious diseases that can cause widespread illness, death, and significant disruption. Evidence suggests that the likelihood of pandemics has increased over the past century. This is due to several interconnected factors. Increased global travel and integration, rapid urbanization, and changes in land use all contribute. Moreover, greater exploitation of natural environments also plays a role. These trends are likely to continue and intensify.

The international community has made strides in preparing for and mitigating pandemic impacts. For instance, the 2003 SARS pandemic and concerns about avian influenza prompted many nations to develop pandemic plans. The World Health Assembly also updated the International Health Regulations (IHR). This was partly due to delayed reporting of early SARS cases. The updated IHR compels member states to meet standards for detecting, reporting, and responding to outbreaks. Consequently, this framework aided a more coordinated global response during the 2009 influenza pandemic.

International donors have also begun investing in improved preparedness. They are refining standards and funding health capacity building. Despite these advancements, significant gaps and challenges persist in global pandemic preparedness. Progress in meeting IHR requirements has been uneven. Many countries struggle to meet basic compliance standards. Outbreaks like the 2014 West Africa Ebola epidemic exposed critical gaps. These included timely disease detection, availability of basic care, contact tracing, and quarantine procedures. Preparedness outside the health sector, including global coordination, also showed weaknesses.

These gaps are particularly evident in resource-limited settings. They pose challenges even for localized epidemics. This has dire implications for what might occur during a full-blown global pandemic. For clarity, an epidemic is defined as cases of an illness occurring in a community or region that are clearly in excess of normal expectancy. A pandemic, therefore, is an epidemic occurring over a very wide area, crossing international boundaries, and usually affecting a large number of people. Pandemics are identified by their geographic scale, not necessarily the severity of the illness. For example, pandemic influenza occurs when a new influenza virus emerges and spreads globally, and most people lack immunity.

Understanding the Immune System’s Defense

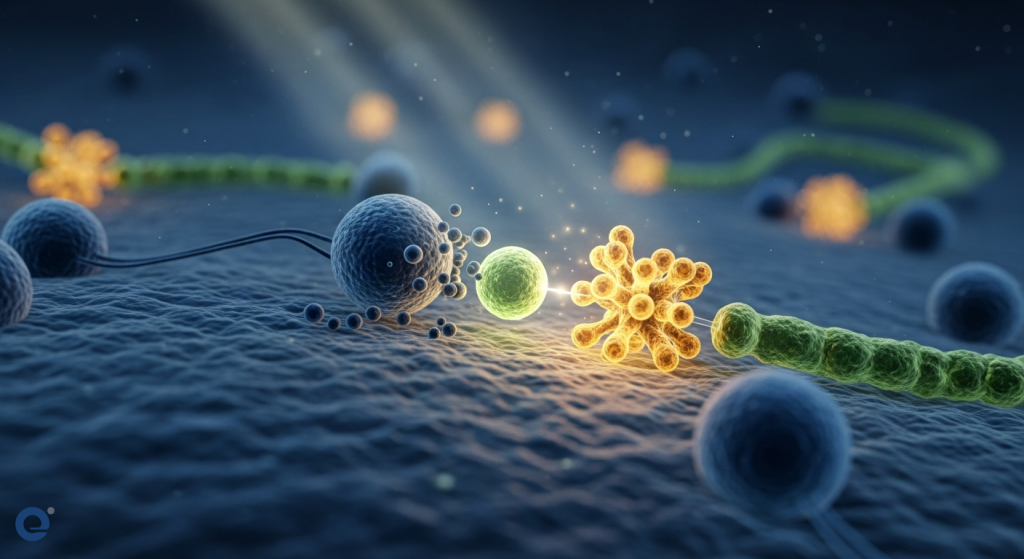

Our immune system is a complex network of cells, tissues, and organs. Its primary role is to defend the body against invaders. These invaders, known as pathogens, include bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites. When a pathogen enters the body, the immune system springs into action. It recognizes the foreign entity and mounts a response to eliminate it.

This defense system has two main branches: the innate and adaptive immune systems. The innate system provides a rapid, general defense. It acts as the first line of defense. The adaptive system, however, is more specific and develops over time. It learns to recognize and remember specific pathogens. This memory is crucial for long-term protection.

The Adaptive Immune Response: Memory and Precision

The adaptive immune response is where vaccines truly shine. It involves specialized white blood cells called lymphocytes. There are two main types: B-lymphocytes and T-lymphocytes. B-lymphocytes produce antibodies. Antibodies are proteins that attach to pathogens, marking them for destruction. T-lymphocytes have various roles. Some directly kill infected cells, while others help coordinate the immune response.

A key feature of the adaptive immune system is immunological memory. After encountering a pathogen, the immune system retains a “memory” of it. This memory is stored in specialized T- and B-lymphocytes. These are called memory cells. If the same pathogen tries to invade again, these memory cells can quickly recognize it. They then trigger a faster and stronger immune response. This prevents or significantly reduces the severity of illness.

How Vaccines Act as Immune System Primers

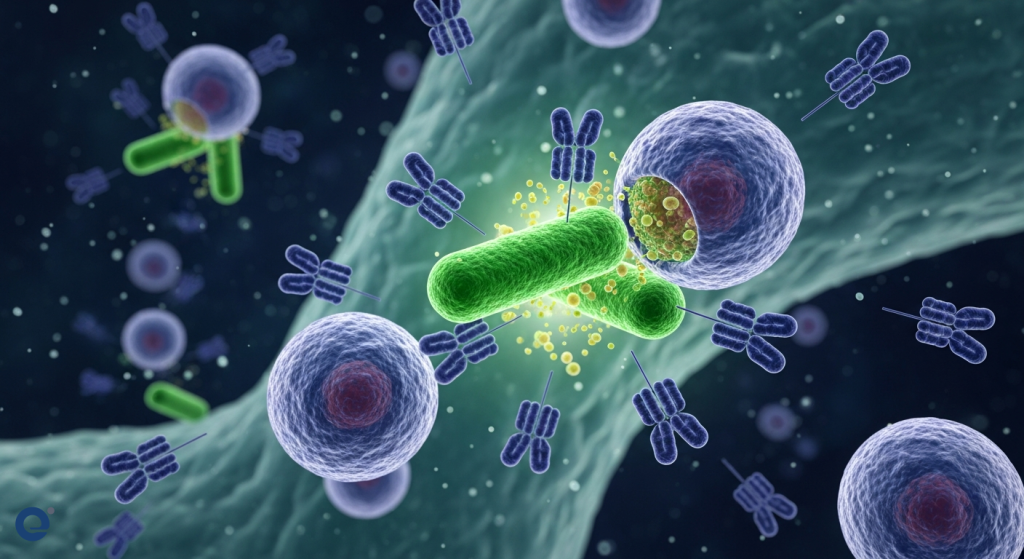

Vaccines work by safely introducing a weakened or inactive form of a pathogen, or a specific part of it, to the body. This process essentially “primes” the immune system. It teaches the adaptive immune system to recognize and fight the real threat without causing disease.

Think of it like a training exercise for your immune system. The vaccine presents a harmless “enemy” to your body. Your immune system then learns to identify this “enemy.” It develops the necessary antibodies and memory cells to combat it effectively. Therefore, if you are later exposed to the actual, dangerous pathogen, your body is already prepared to fight it off.

Different Vaccine Technologies, Same Goal

Over the years, various vaccine technologies have been developed. Each aims to achieve the same goal: to safely stimulate an immune response. Some common types include:

- Inactivated Vaccines: These use a killed version of the pathogen. They cannot cause disease but can still trigger an immune response.

- Live-Attenuated Vaccines: These use a weakened version of the pathogen. They are highly effective but may not be suitable for everyone, such as those with compromised immune systems.

- Toxoid Vaccines: Some bacteria produce toxins that cause disease. Toxoid vaccines use inactivated versions of these toxins.

- Subunit Vaccines: These vaccines use only specific pieces of the pathogen, such as proteins. For example, protein subunit COVID-19 vaccines contain pieces of the spike protein.

- Viral Vector Vaccines: These use a harmless virus to deliver genetic material that instructs cells to make a specific antigen.

- Nucleic Acid Vaccines (mRNA and DNA): These are newer technologies. mRNA vaccines, like some COVID-19 vaccines, deliver mRNA instructions to cells. These instructions tell cells to make a specific protein (e.g., the spike protein). The immune system then recognizes this protein and builds a defense.

For instance, mRNA vaccines use laboratory-created mRNA to teach our cells how to make a protein piece that triggers an immune response. This immune response produces antibodies that protect us from future illness. Importantly, none of these vaccines can give you the disease they are designed to prevent. They do not use live, infectious viruses. Furthermore, vaccines cannot alter your DNA. They do not enter the cell nucleus where your genetic material is stored.

How Do Vaccines Work? | AAP

Vaccines in the Face of Emerging Threats

The emergence of new infectious diseases poses a constant challenge. Factors like increased global travel, urbanization, and environmental changes accelerate the spread of animal viruses to humans. Emerging infectious diseases (EIDs) are a significant threat to public health and global stability.

The rapid development and deployment of vaccines are critical for controlling outbreaks and pandemics. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the importance of swift vaccine development. However, it also underscored the complexities involved. These include manufacturing, distribution, and ensuring equitable access, especially in low- and middle-income countries.

The Challenge of Rapid Development and Distribution

Developing vaccines for emerging threats requires unprecedented speed. This is while maintaining rigorous safety and efficacy standards. Regulatory processes have been streamlined for emergency use authorizations. However, post-vaccination surveillance remains crucial. This is to monitor vaccine safety and track the emergence of new virus variants.

The scale and speed of recent pandemics present new challenges. These affect vaccine developers, regulators, health authorities, and political leaders. Vaccine manufacturing and distribution are complex logistical undertakings. While speed is essential, the entire clinical development process, from emergency use authorization to full licensure, is vital. Pharmacovigilance (monitoring vaccine safety) and surveillance of virus variants are also critical components.

The success of efforts to control current and future pandemics hinges on many factors. These include the ability to rapidly develop and distribute effective vaccines. Equitable access to vaccines must also be prioritized. This is particularly important in lower-income nations. The world population is projected to continue growing, increasing the potential for widespread transmission. Therefore, robust pandemic preparedness, including advanced vaccine technologies, is more important than ever.

Building Immunity: What Happens After Vaccination?

After receiving a vaccine, it typically takes a few weeks for the body to develop full immunity. During this time, the immune system is actively learning and building its defenses. This process can sometimes cause mild side effects, such as fever or fatigue. These symptoms are normal signs that the body is building protection. They indicate that the immune system is responding effectively.

The body is left with a supply of “memory” T-lymphocytes and B-lymphocytes. These cells remember how to fight the specific virus or pathogen in the future. This immunological memory is the key to long-term protection provided by vaccines. Even if a vaccinated person is later exposed to the pathogen, their immune system can mount a rapid and robust response.

Vaccine Efficacy and Effectiveness

Vaccine efficacy refers to how well a vaccine works under ideal, controlled conditions, typically in clinical trials. Vaccine effectiveness, on the other hand, measures how well the vaccine works in real-world conditions. This includes diverse populations and various circumstances. Both are crucial metrics for understanding a vaccine’s public health impact. World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines emphasize the importance of understanding vaccine efficacy and effectiveness to ensure protection. Understanding these metrics is key to public health strategies.

Addressing Vaccine Hesitancy and Misinformation

Despite the overwhelming scientific evidence supporting vaccine safety and efficacy, vaccine hesitancy remains a challenge. Misinformation and disinformation can spread rapidly, leading to unfounded fears about vaccines. It is crucial to rely on credible sources of information, such as public health organizations and scientific institutions.

Open communication and education are vital. Explaining how vaccines work in simple terms can help build trust. Addressing concerns with accurate, evidence-based information is essential. Furthermore, understanding the science behind vaccine development and the rigorous testing processes involved can alleviate anxieties. For those interested in understanding how the body fights off pathogens, exploring the intricacies of immunity and the role of vitamins can provide further context.

The Future of Vaccines and Pandemic Preparedness

The ongoing advancements in vaccine technologies offer hope for tackling future health threats. Innovative approaches, such as mRNA vaccines, have demonstrated the potential for rapid development and adaptability. Researchers are continually exploring new platforms and strategies to create vaccines against a wider range of diseases.

Strengthening global surveillance systems is also paramount. Early detection of emerging pathogens allows for a more timely and effective response. Investing in public health infrastructure and fostering international cooperation are essential components of pandemic preparedness. By understanding how vaccines work and embracing scientific advancements, we can build a more resilient future against infectious diseases.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

How quickly do vaccines start working?

It typically takes a few weeks after vaccination for the body to produce T-lymphocytes and B-lymphocytes, which are crucial for immunity. During this period, the immune system is building its defenses.

Can vaccines give me COVID-19 or another illness?

No, vaccines cannot give you COVID-19 or other illnesses. They do not use live, infectious viruses. Instead, they use weakened or inactive parts of the virus or teach your cells to make a harmless protein that triggers an immune response.

Do vaccines affect my DNA?

No, COVID-19 vaccines do not affect or interact with your DNA. They do not enter the nucleus of the cell where your DNA is located, so they cannot change or influence your genes. Vaccines work by teaching your body to fight the virus.

What are the different types of vaccines?

There are several types of vaccines, including inactivated, live-attenuated, toxoid, subunit, viral vector, and nucleic acid (mRNA and DNA) vaccines. Each type uses a different strategy to safely stimulate an immune response.

Why do I sometimes feel sick after a vaccine?

Mild symptoms like fever or fatigue after vaccination are normal signs that your body is building immunity. These are temporary and indicate your immune system is responding to the vaccine.

How do new vaccine technologies like mRNA work?

mRNA vaccines use messenger RNA created in a laboratory. This mRNA instructs your cells to make a harmless protein piece (like the spike protein of a virus). Your immune system recognizes this protein as foreign and builds antibodies against it, protecting you from future infection. Research into nucleic acid vaccines is advancing rapidly.